When a poet of the stature of Rainer Maria Rilke with such a precise command of words, defined Ronda as the “dreamed-of city”, he had his reasons. Surely after visiting it any traveller will confirm the poet’s judgment, and agree even more the farther he gets from Ronda and remembers it as a dream instead of a place that he has actually touched.

A visitor on his first trip to this city will approach it with mental postcard images of a few of its monuments, its scenery or some of the many characteristic secluded corners that it has to offer, but none of this will serve as a reference or even be easily recognisable because the reality that he will find is very different. Ronda belongs to that select group of towns that can only be compared to themselves, with no possibility of imitation or resemblance to others. This is something that the traveller can prove to himself the moment he enters the historic quarter and sees the dazzling landscape and architecture appear before him, impregnated with history and legend that blur the line between reality and fantasy but that resoundingly affirms the unique character of Ronda.

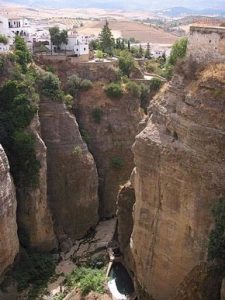

The town is located on a plateau some 750 metres above sea level and seems to be divided into two areas by the famous “Tajo de Ronda” (Ronda Cliff), a gorge 100 metres deep and about 500 metres long with the River Guadalevin running along its floor. The western part of this plateau forms an area of cliffs similar to the one that forms the Tajo itself. Beginning here, an extensive rural landscape opens up that stretches to the mountains that make up the highlands that give the region its name.

The paintings in the La Pileta cave in Benaojan bear witness that the environs of Ronda were inhabited at least since the Paleolithic Period, and remains found in some excavations in the city of Ronda show that there were human settlements in the Neolithic Period. It was the historian Pliny, however, who placed Ronda within the time frame of history when in his writings he refered to the La Arunda of the sixth century B. C. that was inhabited by Bastulo Celts, while identifying the Iberians as being the founders of nearby Acinipo.

The Phoenicians, Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans were later to successively establish themselves, for varying periods, in this area. The Romans named it Laurus and erected the Castillo del Laurel (Laurel Castle, no longer in existence), from which they kept watch over the warlike Celtiberian tribes. Acinipo rather than Ronda was more important in that era, however, as is shown by the fact that it came to mint its own coins.

After the disintegration of the Roman Empire Ronda and Acinipo witnessed the Germanic invasions, and the latter city was even occupied by the Byzantines, who permanently abandoned it in the seventh century when the Visigoths entered Ronda. The city began to acquire a certain political and economic importance with the arrival of the Arabs, who would rename it Izna Rand Onda.

In the late ninth and early tenth centuries, the entire Highlands and especially its capital intensely experienced the insurgency directed from Bobastro (Ardales) by Omar Ben Hafsun against the Caliphate of Cordoba. Later, around the first half of the eleventh century after the fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba, the Berbers made Ronda a Taifas Kingdom, under which the city would experience great urban growth.

The city lost its independence in 1066 when it came under the Kingdom of Seville. Beginning with that date and for almost 400 years Ronda would be dominated by different North African tribes and finally by the Nazarites of Granada. In such a long history, Ronda would know periods of growth and prosperity, stagnation and even regression. Christian troops entered the city in 1485.

Peaceful coexistence between Muslims and Christians did not last very long. The Moorish rebellion broke out and was particularly violent in the Highlands until the expulsion of all Muslims in 1609. As was the case with any town in Málaga, an era of decadence befell Ronda that would last until approximately the eighteenth century, when the city extended into the Mercadillo neighbourhood with the construction of the Puente Nuevo (New Bridge) and the famous Plaza de Toros (Bullring).

French troops under the direct command of Joseph Bonaparte entered Ronda in 1810, an act that set off an unusual guerrilla movement throughout the Highlands. This movement remained alive even after the Napoleonic army abandoned the city in 1812 although it derived from bandit gangs, the most famous of all those in Spain in the nineteenth century which have given rise to so many legends and stories.

With the opening of the railroad in 1891 and the construction of several roads, Ronda entered the twentieth century with a remarkable level of socio-economic development. In 1918 this town was selected for the Andalusian Congress at the urging of Blas Infante of Malaga, who is considered the father of the “Patria Andaluza” (Andalusian fatherland movement).